Rahm, Strokes Gained, EPA, Lefty Patterns, and Bob Voulgaris

Rahm

There is only one golfer on Tour in my database who both gains at least 10 yards per drive on the field and ranks in the Top Quartile by accuracy with driver: Jon Rahm. Fresh off an asymptomatic bout with the coronavirus, Rahm won the 2021 U.S. Open at Torrey Pines this weekend, draining two putts outside of 15 feet on his final two holes. Here’s the putt on #18:

Jon is a ridiculously talented player and one of the most consistent players on the PGA Tour. He will hoist more major championship trophies over the next decade.

Strokes Gained

For decades, golf statistics merely provided a basic overview of a player’s skill set. During the 1990s, players and spectators could only access primitive stats like Fairway Percentage and Average Driving Distance. These statistics do not provide much insight into a golfer’s performance. For example, “Ok, I missed the fairway with my drive. But by how much? Did I miss by six inches or by 20 yards?” Whether you missed a fairway by six inches or by 20 yards, your fairway percentage would be represented as 0/1.

The primitive statistics lack context: There is no context for how your competitors fared nor for how much a missed fairway/green actually affects your score.

Enter Strokes Gained, a statistic developed by Columbia professor Mark Broadie, enabled by a technological system (ShotLink) that tracks the location of players’ shots. The statistic attempts to contextualize the value of a shot. If you watch professional golf, you have probably heard this statistic referenced often. And if you do not understand the details of how the statistic works, do not fret; the commentators do not understand it either.

From a high level, the statistic evaluates a player’s expected score before he hits versus after he hits, and it finds the difference to evaluate the quality of the shot. Here’s a visual representation:

Tiger hits a shot with an iron from the tee box to the fairway, leaving himself 92 yards to the hole. Since the scoring average on the hole is 3.75 and the historical PGA Tour expected value from 92 yards in the fairway is about 2.72, Tiger Woods gains 0.03 strokes on his tee shot. The easiest way to conceptualize the numbers: “After Tiger’s first shot, I would anticipate his expected score to be 2.75, but it was 2.72, so he gained +0.03 strokes on his competitors.”

In theory, the statistic provides context by comparing the quality of a player’s shot to his peers’ shots while answering, “Well how much is that worth?” But in implementation and in interpretation, the statistic has quite a few shortcomings (which is why my partner and I built a dramatically enhanced version of the stat for golfers to use, and we help them draw conclusions).

Today I want to focus on one piece of interpreting the statistic that I have not seen discussed at length: strokes gained reflects the features of a golf course. In the above example, Tiger gained 0.03 strokes:

3.75 (scoring avg. for the hole) – 2.72 (expected value from 92 yards) – 1 = +0.03

What if, in the next round, the scoring average on the hole jumps to 3.95 purely because the flag is in a much more difficult position? Now, Tiger could hit an identical tee shot and he would gain 0.23 strokes:

3.95 (scoring avg. for the hole) – 2.72 (expected value from 92 yards) – 1 = +0.23

Tiger hits identical shots in each scenario, but each shot receives a significantly different strokes gained value.

Consider another example on a fictional golf course.

Let’s predict a fictional player’s performance on fictional Hole 2 and the only data available to us is from fictional Hole 1. For context, when a player hits a shot into the water, his strokes gained on the shot will often be close to -1.25 strokes. Hole 1 has water on both sides of the fairway and there is no water nor a penalty area on Hole 2. Our player hits his tee shot into the water on Hole 1. How do we predict his strokes gained for his tee shot on Hole 2?

Does it make sense to predict that on Hole 2 without penalty areas, our player will lose 1.25 strokes on his tee shot? It’s not possible. The player might hit into a bad location where he loses ~0.5 strokes, but if the hole does not have any penalty areas, he cannot lose more than ~0.5-0.6 strokes. Yet many models predict future strokes gained numbers by averaging past strokes gained numbers.

Golfers do not play all the same courses. In comparing most statistics across golfers and across courses, people neglect how the characteristics of a course impact the data and predictions about the future.

I want to emphasize two points:

Statistics (including Strokes Gained) often reflect other factors, which is especially impactful in the short term

It’s valuable to use statistics while remaining cognizant of their pitfalls

“How does this stat work? What does it fail to contextualize?” is a worthwhile mental exercise

Expected Points Added

For decades, football statistics merely provided a basic overview of a player’s skill set. In previous decades, players and spectators could only access primitive stats like Passing Yards per Game and Yards per Rushing Attempt. These statistics do not provide much insight into a player’s performance. For example, a quarterback might throw for 350 yards, but is this the result of stellar play or a function of being down by 20 points all game and throwing 25 times in the second half? The primitive stats lack context.

Enter Expected Points Added (EPA) per play, a statistic designed to contextualize plays in the NFL. From a high level, the statistic evaluates your expected points before a play versus after a play, considering field position, down and distance to a first down, and game clock. This statistic is basically the football equivalent of Strokes Gained in golf.

“From your own 20-yard line, an 8-yard gain on third-and-10 is worth about minus-0.2 EPA because you don't get a first down; the same 8 yards on third-and-7 is worth 1.4 EPA for converting a long third down and keeping the drive alive. EPA knows that not all yards are created equal.”

Like Strokes Gained, Expected Points Added per play has an obvious appeal. The stat provides context and solves for some of the deficiencies of basic stats like Passing Yards per Game. However, perhaps more than Strokes Gained, EPA per play should be interpreted thoughtfully. Using the above example, an 8-yard gain on third-and-10 from your own 20-yard line reflects negatively. That play did not increase your team’s chance of winning. Fair enough.

But this statistic is frequently used to evaluate the play of individual skill players like quarterbacks. In the above example, what if the quarterback made a perfect read and delivered a perfect throw for an 8-yard gain? To what extent is EPA per play reflecting other factors like defensive scheme and offensive play-calling?

I am particularly drawn to this concept with the example of Jameis Winston, who ranked 14th (about average) among quarterbacks in EPA per play in the 2019 NFL season. He also led the NFL in interceptions by nine(!) during that season. Winston was involved in many really good plays and many really bad plays.

Imagine Jameis Winston throws an 80-yard touchdown pass on one possession, and then throws three straight incompletions his next time on the field. Per play, probably not a bad average over those four plays. Now imagine Tom Brady orchestrates an 80-yard drive, consistently gaining 5-10 yards per play over the course of 10-15 plays. Per play, probably not a great average. From an EPA per play perspective, I am skeptical that the stats associated with each respective scenario accurately reflect the quality of each quarterback’s play.

Statistics are enlightening. So is understanding/adjusting for their limitations.

Left-Handed Dispersion Patterns in Golf

One way to visualize part of a professional golfer’s skill set is to chart her tee shots. You can observe how close a player hits shots to the intended target, and you can also see how often a player misses to the left or to the right of her target. Golf statisticians refer to these charts as dispersion patterns.

Depth is an interesting element of a dispersion pattern; some players hit the ball farther or shorter when missing right or left. Generally speaking, when a right-handed player pulls the ball (results in missing a target to the left), she hits the ball farther than when she pushes the ball (results in a right miss). This is not true of every golfer, but it is true of Phil Mickelson. Phil is left-handed, so pulling the ball results in a miss to the right of his target. I ran the numbers, and Mickelson hits the ball about 15 yards farther with driver when he misses right versus when he misses left.

A few weeks ago, I listened to Jim “Bones” Mackay, Phil’s longtime caddie, discuss this concept on the No Laying Up podcast. One of the most prominent examples of this concept in action is Hole 12 at Augusta National:

When a right-handed player aims at the pin on this hole, his miss will typically end up short right, which often repels back into the water. In the 2019 Masters, several right-handed contenders (Molinari, Koepka, Finau, and Poulter) all found the water on Sunday, contributing to Tiger Woods’ historic victory. For a left-handed player, a miss will typically come up short left in the sand trap or long right – neither location results in a penalty stroke. This hole sets up advantageously for a left-handed player.

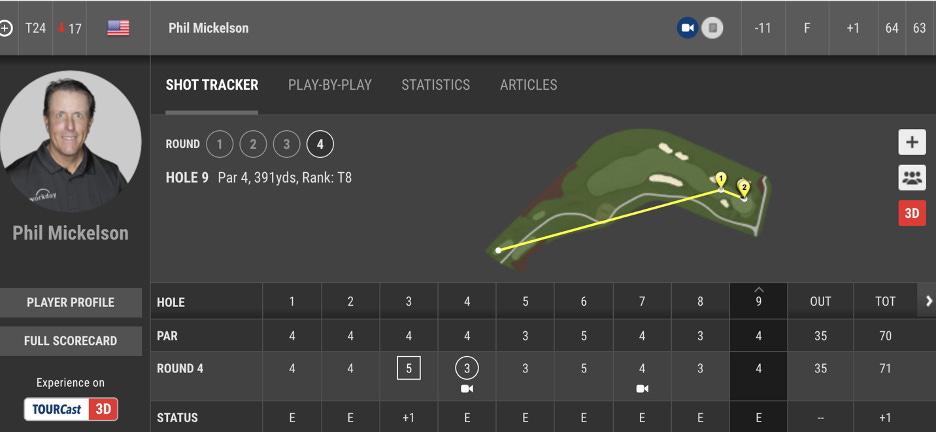

This upcoming week, the PGA Tour heads to the Travelers Championship at TPC River Highlands golf course. Mickelson has committed to playing in the tournament. You can make a compelling argument that Hole 9 at TPC River Highlands sets up well for Phil Mickelson from a dispersion perspective:

Look at how the shape of the fairway fits Phil’s dispersion pattern. If he flares a shot out to the left, the ball does not have to travel quite as far to find the fairway. If Phil pulls the ball (to the right), the increased distance will fit the shape of the fairway. He has a bit of a diagonal dispersion pattern, which fits the shape of the hole.

Mickelson has only played this hole six times in the last ten years, but he has hit the fairway every time and it is one of his best performing holes at TPC River Highlands. I’m cautious about drawing conclusions from such a tiny sample, but it is an interesting concept for you to observe this week.

Bob and the Mavs

Shortly following the Dallas Mavericks first round exit from the NBA Playoffs, problems began to unravel. An Athletic article outlined controversy surrounding Haralabos (Bob) Voulgaris, then Mark Cuban fired longtime General Manager Donnie Nelson, then longtime coach Rick Carlisle resigned.

Who is Bob Voulgaris? Bob is a legendary basketball gambler from humble beginnings in Canada. He started watching NBA basketball with an analytical eye, and he eventually became (arguably) the best basketball bettor of all time. Safe to say, he has made millions betting on the NBA. The professional gambling community is not the warmest conglomeration, and I am always struck by how much reverence professional gamblers show for Bob: He’s incredibly smart and accomplished.

In 2018, Mark Cuban hired Bob Voulgaris to oversee the analytical wing of the Mavericks. He is not the GM, but he clearly has Cuban’s ear. And why wouldn’t he? Bob probably knows as much as anyone on the planet about what drives success in the NBA.

According to The Athletic, many people within the Mavs organization despise him. There are rumors of Voulgaris making unilateral decisions and rubbing people the wrong way in the process. He’s been described as a “shadow GM” and rumored to be dictating specific rotations for Coach Carlisle to use, which Cuban vehemently denied on Twitter.

Most notable among the alleged Voulgaris haters is Luka Doncic, the 22-year-old superstar and future of the Mavericks. On a podcast with Zach Lowe, ESPN’s Tim MacMahon dropped a wild anecdote about a Mavs game earlier this season. There were no fans in attendance due to Covid restrictions, so anyone present in the arena could hear players and coaches talking. With Voulgaris seated in the front row, a frustrated Doncic yelled at Coach Carlisle, “Who is in charge: You or Bob?”

I’m interested in seeing how this unfolds. What an interesting balancing act! I don’t think Cuban wants to lose Bob. I know Cuban doesn’t want to lose Luka.

Contact/Feedback

Email: Joseph.LaMagnaGolf@gmail.com

Twitter: @JosephLaMagna

Other Content I Enjoyed this Week:

Katie Ledecky is one of the most dominant athletes in the world right now: